Walking the length of Manhattan (Part 2)

From 175th Street to 50th Street

Much more than a week has passed since I promised you the second installment. I wish I could claim that I spent that time contemplating the 125 blocks that follow, writing and revising to give my reader 1,500 words of cogent, comprehensible prose. Instead, you are getting stream of consciousness reflections patched around the outline I wrote more than a month ago. At least the pictures are interesting.

In my last post, I alluded to why I decided to walk the length of Manhattan. But there is another nested “why” that went unaddressed — why did I walk the length of Manhattan along Broadway?

The answer is more logistical than philosophical — I usually exhaust my decision-making abilities at work and the thought of going down any possible permutation of the grid made the enterprise sound more daunting than appetizing. Unfortunately, no street has the gaul to run the length of Manhattan…except for Broadway, which predates the grid and was somehow not squashed by it. Today, it starts at Battery Park and runs into the Bronx.

Given Broadway drastically limits the option set of contiguous roads in Manhattan, this walk is by no means “unique.” If anything, I am surprised it’s not more of a pilgrimage. Entire books have been written on it and there is a wide body of self-indulgent blogs, to which yours truly is gleefully adding.

None of these writings betray any sense of their own exceptionalism. Everyone does seem to know we are being derivative. On one such blog, the author replaced his ‘about me’ blurb with a comment he received on the internet:

“[What he's doing] has been done before why is this even relevent (sic). [Bruce Smith is] another person with too much free time, not enough friends and a need for attention [who goes] for a walk. The end.”

The fact that we all do the walk anyway is a testament to the allure of the City. For me, it wasn’t about the “feat” itself (walking 13 miles is hardly pushing human limits) but the prospect of spending six hours deeply immersed in the continuum of blocks that make this island. I had visited almost each one of these neighborhoods before, so little was truly “novel.” But I had earlier perceived these neighborhoods as discrete units with their own quirks and characteristics. During the walk I was able to feel how the landscape changed across ten, twenty, and hundred blocks and develop an intuition for the continuum.

Hour 1: 175th Street to 122nd Street

Last time I left you at United Palace on 175th street. At 168th street, Broadway stops dashing across the grid to become a part of it for ~90 blocks, running parallel to Amsterdam Avenue till 79th Street where it swerves again to give rise to a string of interstitial landmarks — Columbus Circle, Times Square, Madison Square Park, Union Square.

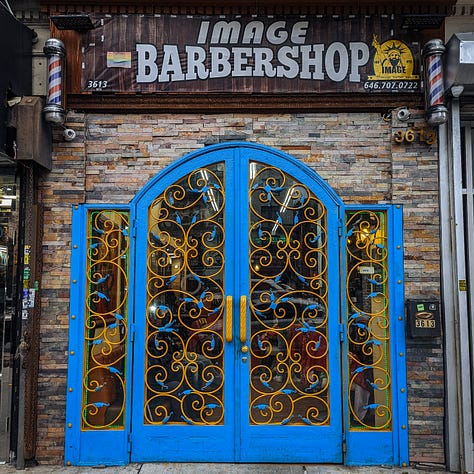

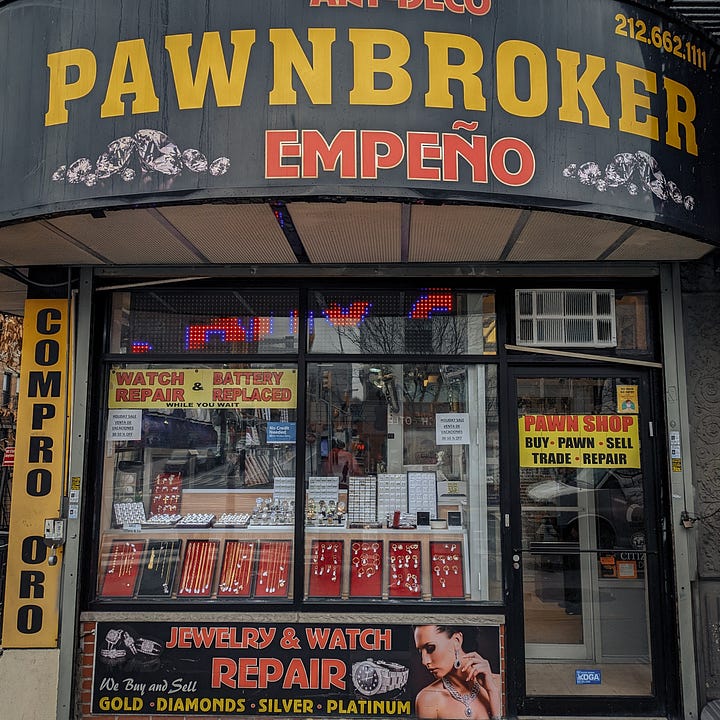

From 175th to 122nd, three kinds of institutions in particular stuck out to me: pawnshops, laundromats, and barbershops.

There are many things that differentiate affluent neighborhoods from impoverished ones. The prevalence of seemingly predatory financial institutions has been on my mind for a while. For a long stretch through upper Manhattan, every few blocks housed a pawnbroker. Many storefronts for electronics and furniture proclaimed cheap financing on their awning. I go back and forth on how I feel about such institutions – they provide liquidity and capital to populations the formal financial system won’t touch, but do they also have a vested interest in maintaining the unequal status quo as a result? I feel ambivalent because it feels easy to paint all small time pawnbrokers as loan sharks (and popular culture often does). However this representation might also absolve us of the duty of trying to make money more equal.

I saw a smattering of all sorts of name brand and chain stores over this walk, but laundromats and barber shops / salons uniquely stood out as being universally small, independent businesses. I was especially amused by laundromats, which to my consulting brain feel very easily commodifiable, but seemed to be largely run by family establishments. How have these institutions avoided being turned into chains? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Near 133rd street, the landscape changed from familiar six-storey blocks to giant Corbusier-esque housing complexes. 3333 Broadway (Riverside Park Community) particularly blew my mind in its scale and size.

As I approached 125th street, I passed close by my first(!) digs in the City. When I lived in the area, The Forum was still under construction. I can’t say I instinctively loved seeing the completed building, which looked eerily like the renovated parts of Sterling and Bass at Yale, but I haven’t learnt enough about how the building came to be to have a more informed opinion.

Near 122nd Street, I took my only prolonged detour off Broadway, onto La Salle St to pass by Kuro Kuma, a coffee shop I encountered during my first tryst with New York in summer 2019, when I lived in Columbia housing while working my first corporate internship in Hudson Yards. After three years of college, I was not used to the routine that comes with a rush hour commute and I savored it. For the first time in my life, I used to wake up before I needed to so I had enough time to pick up an iced coffee at Kuro Kuma and snag a seat on the 1 so I could read in peace. I vividly remember the one barista who was the first person I talked to for ~60 mornings that summer. I don’t think I ever got his name but our interactions were emblematic of what I love about NYC — we “knew” each other even if we never feel the need to converse. He remembered my order and I felt comforted by the regularity of his preparation. Kuro Kuma never qualified as a friendship but it provided me community for a summer.

Hour 2: 122nd Street to 79th Street

After my coffee break I entered a little bit of a slump – I felt like I had already walked a lot but I still had so much to go 😯.

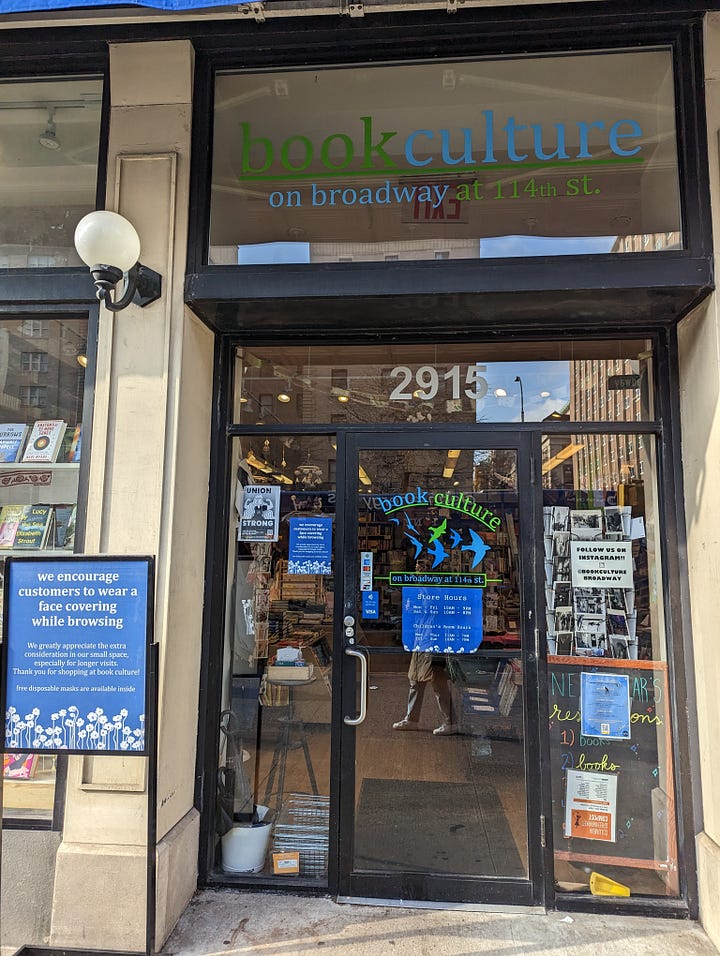

I don’t remember too many details about this part of the walk. I saw some lovely collegiate gothic in Columbia buildings. I passed by Book Culture, my favorite book store in the area, where I once experienced a classically New York act of kindness – I was stuck in the store during a torrential summer downpour, happily browsing but visibly fidgeting because I was getting late for dinner. Out of her own volition, the storekeeper handed me an umbrella and sent me on my way. I don’t recall any words being exchanged.

As Morningside Heights gave way to the Upper West Side, the landscape turned into large, early 20th century apartment blocks — from when the elevator had just been commercialized and the rich had started moving northwards. I saw many more huge apartment buildings, with one, the Belnord, spanning an entire block. It’s one of a handful of block-size apartment buildings in the City.

These huge buildings felt a little less daunting than the ones I had passed around 133rd. In fact, I hadn’t realized many of them were so huge all the other times I had passed through this area (the Belnord even has a giant private courtyard in the middle!). They are well-modulated by other medium rise buildings and do not stand apart in the landscape. There are two kinds of big buildings – those designed to amaze and those whose bigness should be invisible. I like monuments that do the former, but they should be few and far between. I appreciated these buildings for doing the latter.

Hour 3: 79th Street to 50th Street

For a few blocks after 79th Street, I realized I was passing through New York’s early 20th century Billionaire’s Row. The Apthorp encloses a block-size courtyard, The Ansonia is the “truest” Beaux-Art apartment building I’ve seen in the city. The buildings were extraordinarily ornate and embellished and vast, though still generally human scale. I saw the spires of the present-day Billionaire’s Row along 57th Street soon after, and thought of how the conspicuous residence of the wealthiest among us has changed over time. While the “latest technology” (then elevators, now supertall towers) has always been in vogue with the rich, I sometimes wish the new age buildings gave me more visible detail to marvel at and appreciate craftsmanship that exists beyond “simply” defying gravity.

At 66th Street I passed Lincoln Center, which I think is one of the nicer built public spaces in the City. However, a few months earlier I had watched Straight Line Crazy, a play on the life of Robert Moses, long-time New York City Parks Commissioner and “Power Broker” in the 1920 through 60s. Moses had led a slum clearance campaign to make land for Lincoln Center, which was subsequently endowed by a Rockefeller (I couldn’t be bothered with figuring out which one). Moses also propagated an urbanism that was car-centered, racist, and non-human scale. But he also made Lincoln Center possible. Almost a century on, how can I separate the building from the builder?

Near the northern limits of Time Square, where the neon lights barely make the sidewalks glow during the day, I took my second and last protracted break at a WeWork. Logistical side note: it’s quite hard to plan around public bathrooms during an urban hike. And so, I ended up at a workplace on my day off. I had never been to this particular WeWork location before but I could navigate it almost instantly. Even though the designers had incorporated some nods to Times Square in the decor, the overall aesthetic painfully mirrored every other WeWork I had ever been to (over 20). The first half of my walk had made me feel incredibly rooted in place, but during my half time break I felt like I could’ve been anywhere.

Addendum: Notes on predatory finance in Matthew Desmond’s latest book:

“The short answer, Desmond argues, is that as a society we have made a priority of other things: maximal wealth accumulation for the few and cheap stuff for the many. At the same time, we’ve either ignored or enabled the gouging of the poor—by big banks that charge them stiff overdraft fees, by predatory payday lenders and check-cashing outlets of what Desmond calls the “fringe banking industry,” by landlords who squeeze their tenants because the side hustle of rent collecting has turned into their main hustle, by companies that underpay their workers or deny them benefits by confining them to gig status or that keep them perpetually off balance with “just-in-time scheduling” of shifts. To the extent that middle- and upper-class people unthinkingly buy products from such companies and invest in their stock, or park their money in those banks, or oppose public housing in their neighborhoods despite a professed commitment to it, or bid up the prices of fixer-uppers in Austin or San Francisco or Washington, D.C., they, too, are helping to buttress the system.”

https://archive.ph/2023.03.13-112526/https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/03/20/matthew-desmond-poverty-by-america-book-review